Book news from a world at war

Sometimes even numbers play tricks. On 25 April, in Italy, we will celebrate the anniversary of the liberation from Nazi-fascism. This will mark the first two months since the start of the war in Ukraine, which Putin unleashed – according to him – precisely to fight the neo-Nazis.

With regard to the conflict, 7 April saw the release of Nella mente di Vladimir Putin, an eBook published by La Nave di Teseo by Elena Kostioukovitch. A writer and translator into Italian and Russian, she has been a naturalised Italian since 1996, but her roots lie in Kiev, where she was born. Kostioukovitch tries to make readers understand ‘the real cause of the war against Ukraine’, namely the birth and spread of the ‘doctrine of the Russian Universe’.

Also on 7 April, Ukraine 24.02.2022, an instant book by Il Sole 24 Ore on the causes and consequences for Europe of the war between Russia and Ukraine, was released in bookshops.

The texts do not come as a surprise, since Italy immediately took sides in favour of peace in Ukraine, implementing a policy of excluding Russia even from the cultural world.

Walls of war

A few days after the start of the conflict, in fact, the promoters of the Festival of European Photography in Reggio Emilia announced the cancellation of Russia’s participation as guest country: ‘Art and culture should always build bridges and not erect walls; however, they cannot retreat into ivory towers. There is a time to firmly affirm the right of peoples to live in peace and a time to open up to dialogue and confrontation, without violence and death being invited to the table’.

Among the excluded artists, the case of Alexander Gronsky, arrested in Moscow at the start of the invasion precisely because of his anti-war protests, caused a stir. However, the Russian photographer sided with the Festival organisers’ decision, because ‘no one wants to have anything to do with a terrorist state’, even if culture always remains ‘the main bridge we have between peoples’.

Milan and Bologna

A few days after the Reggio Emilia case, the Bicocca University in Milan also caused quite a stir, after the decision to cancel a short course of four lectures on Dostoevsky held by Paolo Nori, a writer and scholar of Russian literature. Following Nori’s protests, the Bicocca gave the course the go-ahead, provided it also included some Ukrainian authors. The university’s hasty and bungled retreat resulted in a sharp rejection by Nori, who declared in astonishment: ‘Being a Russian is a guilt. So is being a dead Russian’.

In the same days, the Fiera del Libro per Ragazzi di Bologna suspended cooperation with official Russian organisations in favour of promoting Ukrainian publishers, books, illustrators and authors. However, the President of the Italian Publishers’ Association Ricardo Franco Levi reiterated his support for the Russians who ‘signed an appeal in favour of peace and an end to military operations in Ukraine, thus demonstrating their dissent from President Vladimir Putin’s choices’.

Censored literature?

However, the most striking case was the one involving the Voland publishing house, which has shown a keen interest in Slavic literature since its inception. Its founder Daniela di Sora allegedly received an e-mail, sent by some Ukrainian cultural institutions, with an invitation to boycott Russian books. Di Sora said she was shocked by the episode: ‘I choose books that, from my point of view, have a value. Whether this value is historical, social, political, anthropological, of custom, this can very well be decided by the reader’. He also pointed out the genesis of the name of his publishing house: ‘The name Voland comes from Bulgàkov, who as we know was born in Kiev and died in Moscow: in our catalogue there are Russian authors and books by Ukrainian authors. Literature unites, creates bridges’.

The exceptions

However, there have been numerous exceptions to these cases of ‘censorship’ (which have also involved major cultural foundations such as the Biennale di Venezia and the Teatro Petruzzelli in Bari). Eike Schmidt, director of the Uffizi, decided not to close the Museum of Russian Icons in the Pitti Palace. Nicola Lagioia, director of the Turin Book Fair, declared that he would not boycott Russian authors, despite the absence of official delegations linked to the Russian government. Gian Maria Tosatti, artistic director of the Quadriennale di Roma, strongly condemned cultural bans and censorship, calling them ‘the antechamber of war’.

“The show can’t go on”, headlines The Guardian: whether we choose to agree with one side or the other, the consequences of this war are inevitably affecting even the art world, which should instead be super partes and promote messages of peace, beauty and universal brotherhood.

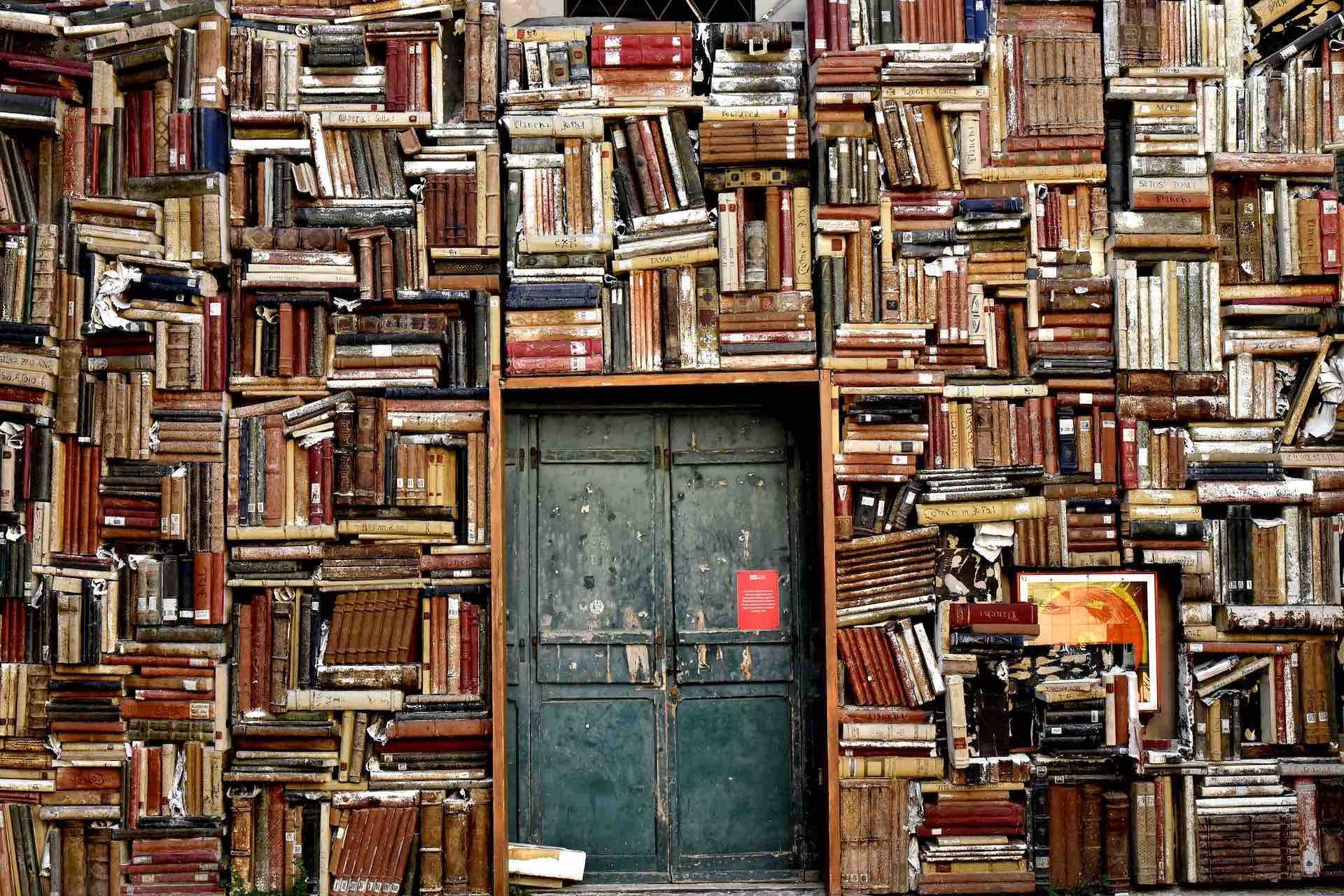

Perhaps it is in Ukraine that we can find the most powerful answer to this cultural disintegration. “The Kiev Wall of Books” is a photograph taken by urban architect Lev Shevchenko that has become iconic on the Web. It depicts the exterior of a house in which books have been erected in front of the window, probably to protect against glass breakage.

A contemporary metaphor of how literature can defend us from the inhumanity of war, declined in all its forms: disinformation, ignorance, censorship and the destruction of what makes us profoundly human.